The debate over whether a long-term vegetarian diet is healthier has been ongoing for decades. While some swear by the benefits of plant-based eating, others warn of potential nutritional deficiencies. The truth, as with many dietary questions, lies somewhere in between and depends largely on how the diet is implemented.

The rise of vegetarianism has been fueled by various factors, including ethical concerns, environmental awareness, and health considerations. Many studies have shown that well-planned vegetarian diets can offer numerous health advantages, such as lower risks of heart disease, hypertension, type 2 diabetes, and certain cancers. The high fiber content and abundance of phytonutrients in plant foods contribute to these protective effects.

However, the key phrase here is "well-planned." Simply eliminating animal products without proper substitution can lead to serious nutritional gaps. Protein, for instance, is often the first concern that comes to mind. While plants do contain protein, they generally lack one or more essential amino acids that the body cannot produce on its own. This makes protein combining across different plant sources crucial for vegetarians.

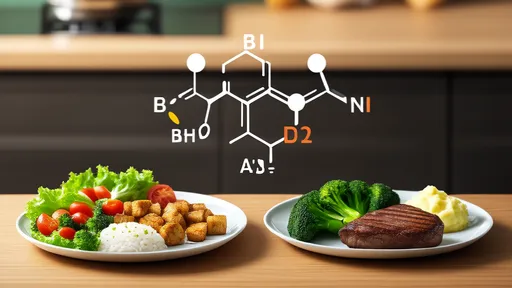

Vitamin B12 deficiency represents one of the most significant risks for long-term vegetarians. This nutrient, essential for nerve function and blood cell formation, is naturally found only in animal products. While some plant foods are fortified with B12, supplementation is often necessary. Neurological damage from B12 deficiency can be irreversible, making this a particularly serious concern.

Iron presents another challenge. While plants contain iron, it's in the non-heme form which is less bioavailable than the heme iron found in animal products. Vegetarians need to consume significantly more iron-rich plant foods and should combine them with vitamin C sources to enhance absorption. Symptoms of iron deficiency include fatigue, weakness, and impaired immune function.

Omega-3 fatty acids, particularly DHA and EPA which are crucial for brain health, primarily come from fish. While the body can convert ALA (found in flaxseeds and walnuts) into these active forms, the conversion rate is inefficient. Algae-based supplements have emerged as a potential solution for vegetarians concerned about maintaining adequate omega-3 levels.

Zinc, calcium, and vitamin D are other nutrients that require special attention in vegetarian diets. Phytates in many plant foods can inhibit zinc absorption, while calcium from plant sources may be less bioavailable. Vitamin D, which works synergistically with calcium, can be particularly challenging to obtain without fortified foods or supplements, especially in regions with limited sunlight.

The psychological and social aspects of long-term vegetarianism shouldn't be overlooked. Dietary restrictions can sometimes lead to orthorexic tendencies or social isolation in food-centric gatherings. The mental health implications of strict dietary regimes are an emerging area of research that warrants consideration alongside physical health outcomes.

Interestingly, the health impacts of vegetarian diets may vary by individual. Genetic factors influence how people metabolize different nutrients, meaning the same diet could affect two people quite differently. Emerging nutrigenomic research suggests that some individuals might be genetically better suited to plant-based diets than others.

Life stage considerations add another layer of complexity. While adults might thrive on vegetarian diets, children, pregnant women, and the elderly have unique nutritional needs that make balanced vegetarian eating more challenging. Pediatric nutrition experts emphasize that vegetarian children can grow normally, but their diets require careful planning and monitoring.

The quality of vegetarian food choices makes a tremendous difference. A diet heavy in processed vegetarian alternatives (like fake meats) and refined carbohydrates would likely be less healthy than one centered on whole foods, regardless of its animal product content. The Mediterranean diet, which includes moderate amounts of animal products but emphasizes plants, often outperforms strict vegetarian diets in health outcomes.

Cultural and geographical contexts also matter. Traditional vegetarian diets from cultures with long histories of plant-based eating (like in parts of India) have evolved to include complementary proteins and preparation methods that enhance nutrient availability. Adopting vegetarianism without this cultural knowledge base can lead to poorer outcomes.

Environmental contaminants represent an underdiscussed aspect. Some research suggests that vegetarians might have higher exposure to certain pesticides and heavy metals from increased consumption of produce. This isn't an argument against vegetarianism, but rather a reminder that all dietary patterns have trade-offs that must be managed.

Ultimately, whether a long-term vegetarian diet is healthier depends on how it's practiced. With careful planning, supplementation where necessary, and attention to food quality, vegetarianism can certainly support excellent health. However, it requires more nutritional knowledge than omnivorous eating to avoid deficiencies. For many, a flexible approach that includes high-quality animal products in moderation might offer the best balance of health benefits and nutritional adequacy.

The decision to adopt vegetarianism should be based on individual health needs, ethical considerations, and the willingness to maintain the diet properly. Consultation with a nutrition professional can help identify potential pitfalls and create an eating plan that delivers all necessary nutrients while aligning with personal values and health goals.

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 15, 2025

By /Aug 15, 2025

By /Aug 15, 2025

By /Aug 15, 2025

By /Aug 15, 2025

By /Aug 15, 2025

By /Aug 15, 2025

By /Aug 15, 2025

By /Aug 15, 2025

By /Aug 15, 2025